Written somewhere over the Alps en route to Provence

--Much of the process of photography can be distilled into these:

- A process of the hands, a reflex – an act of gesture, a kind of muscle memory, an extension of the arm

- A process of contemplation – an extension of the retina.

Photography as gesture: an extension of the hand

At first, it seems implausible how a work of art can reside in something as “pedestrian” as a gesture – something more associated with a handyman than an artist. Yet it is precisely this that makes it fascinating: that artists elevate manual labour into art. This is as true for a chef, as for a photographer. It is no wonder chefs will laboriously train in their fine motor skills.

Yet it is precisely this that makes it fascinating: that artists elevate manual labour into art.

Photography, akin to muscle memory, is largely driven by speed and reflex. If a significant aspect of photography hinges on capturing the decisive moment—as Cartier-Bresson referred to that perfect instant to press the shutter—then this reflexive nature of photography becomes even more critical.

Imagine a photojournalist witnessing a scene unfold within a second or two, instinctively responding in that split second. Their camera is an extension of their body, seamlessly integrated into their movements. In that brief moment, they raise the camera to the perfect height, angle it correctly, adjust the composition and framing, tilt the frame as needed, focus on the right part of the scene, and ensure the exposure is accurate.

There is no thought in any of these actions, at least, no thought on a conscious level, as much as there isn’t conscious thought in any reflex. Just as you automatically move your hand away from a hot surface, the photographic reflex is swift, subconscious, and automatic. The camera’s job is to facilitate this process, becoming an extension of the hand and retina, seamlessly integrating with the eyes and hands.

For this to happen, the camera must operate predictably, earning the photographer’s trust as much as their own eyes. You point, you shoot, and that’s all there is to it.

I have used many cameras in my life, and some have integrated better with my hand. My GFX with a manual lens excelled at this, allowing me to manually focus throughout an entire wedding. However, as my eyes grew tired, the manual focusing became more of a hindrance, slowing me down and causing me to second-guess each frame. It shifted from being a natural gesture or reflex to a more conscious and deliberate process. It no longer was as much of a gesture, a reflex, but a conscious process.

Here, a parenthesis is needed. While one school of thought emphasizes the importance of being intentional about every picture taken—much like a studio portrait photographer—there is another approach where the camera is used as a tool for automatic expression. In this sense, akin to André Breton’s use of automatic writing, the camera becomes a means to express the subconscious without censorship or rational control, or a tool for Dada and abstract expressionism, a medium for spontaneity, improvisation, and the desire to break free from traditional formalism.

But as for myself, I prefer finding a balanced middle ground rather than embracing extremes. Therefore, how can a camera seamlessly transition between being a medium for formal structuralism and a tool for automatic expression, precisely when needed? If you think of driving, it is both a process of very precise control as well as subconscious reflex. That’s exactly what I am looking for in a camera!

If you think of driving, it is both a process of very precise control as well as subconscious reflex. That’s exactly what I am looking for in a camera!

Cameras like most modern mirrorless cameras excel as gestural tools due to their compact size (especially with lightweight lenses), quick autofocus guided by artificial intelligence, and strong capabilities in exposure and white balance adjustments. To enhance their gestural, automatic, reflex-like nature, I have a trick: with every camera I use, regardless of brand, I switch the live view to black and white. This eliminates distractions from colors. I set it to auto-expose and auto white balance. All I need to do is frame, focus, and click—a truly instinctive process. Additionally, I minimize distractions by disabling custom buttons and simplifying the screen to remove elements like levels and rule-of-thirds guidelines that might interrupt my flow of shooting.

If you consider cars, they’re designed with enough similarities that you can switch between them and still drive safely and comfortably. Unfortunately, the same can’t be said for cameras. Apart from a few common design elements like the shutter button or an AEL button, modern cameras vary enough to disorient you when you switch between them. In contrast, older analog cameras are much simpler. They have fewer customizable features, and their buttons are more consistent across different models and brands. I wish modern cameras could have this same simplicity.

Give it a try! Disable all unnecessary custom buttons (even though it might feel like you’re limiting the camera’s potential, it’s akin to losing one sense and heightening others). Minimize the information displayed on the screen as much as possible. Most importantly, convert the display to black and white. Now, regardless of which camera you pick up—whether it’s a Leica, Sony, Fujifilm, or Canon—apart from ergonomics, it will essentially be the same device: a black and white screen with a button. Go on, and simply trust the machine, the process, and yourself!

Photography as contemplation: an extension of the retina

If certain occasions require the photographer to act reflectively, other rely more on the act of “seeing”. To be honest, the distinction is not exactly as clearcut. How fast does the photographer need to respond to the stimulus might be a better way of describing this: is it as fast as a reflex, or is it slow, like an exploration? Some might call the latter “intentional”. Intentional, seems to be a buzzword nowadays, but I want to avoid using it because it is often misused to declare a qualitative distinction, as in “intentional photography” being better than photography as a reflex. Firstly, photography as reflex, vs a slower explorative seeing of the world, both contain some intentionality – they just happen at different speeds. . Secondly, can anyone argue that the iconic photograph “The Terror of War,” by Nick Ut, depicting a young Vietnamese girl fleeing a napalm attack, captured in an instant reflex, is any less a masterpiece than a meticulously crafted Vogue cover? I believe, intentionality has less to do with speed, and more with artistic maturity.

I believe, intentionality has less to do with speed, and more with artistic maturity.

I enjoy when my camera becomes an extension of my hand, responding gesturally to my movements, yet I also value its role as a microscope—a tool that allows me to isolate and explore scenes slowly. For instance, I appreciate manual focusing because it lets me actively engage in exploring a scene. As I adjust the focus ring, different elements gradually come into clarity, revealing themselves to me. Instead of deciding beforehand what to focus on, I prefer the freedom to explore, watching various objects shift into focus as I visually “walk” through the scene.

Similarly, I choose to disable focus peaking because it directs attention towards “getting the focus right,” which can distract from the exploration of the scene itself. I would rather immerse myself in exploring the scene, even if it means occasionally missing perfect focus.

If you think about this a bit more, this is not an outrageous notion: Leica rangefinders, as an example, highlight the exploration and contemplation as one of their strengths—the viewfinder shows more of the scene than what will be captured. They claim this allows you to explore more, as you anticipate people entering the frame and be better prepared, preventing isolating the world within a small viewfinder. For Leica, this contemplative, explorative nature of the rangefinder is a selling point!

Photography in “two speeds”: a dance of relfex and contemplation

Here is how I set my cameras “on two speeds” either slowing down or speeding up, at will. When I buy a new camera, my goal is to set it up in the simplest manner as possible:

– The display is B&W, with as little information as possible

– Almost all buttons are disabled

– I setup a back-focus button for autofocus

– The default state is manual focus, meaning, the shutter button does not trigger autofocus, and the focus ring on the lens enables manual focus.

That’s all! This is how my camera gets its “two speeds”: an extension of my hands, and, an extension of my retina.

Notes:

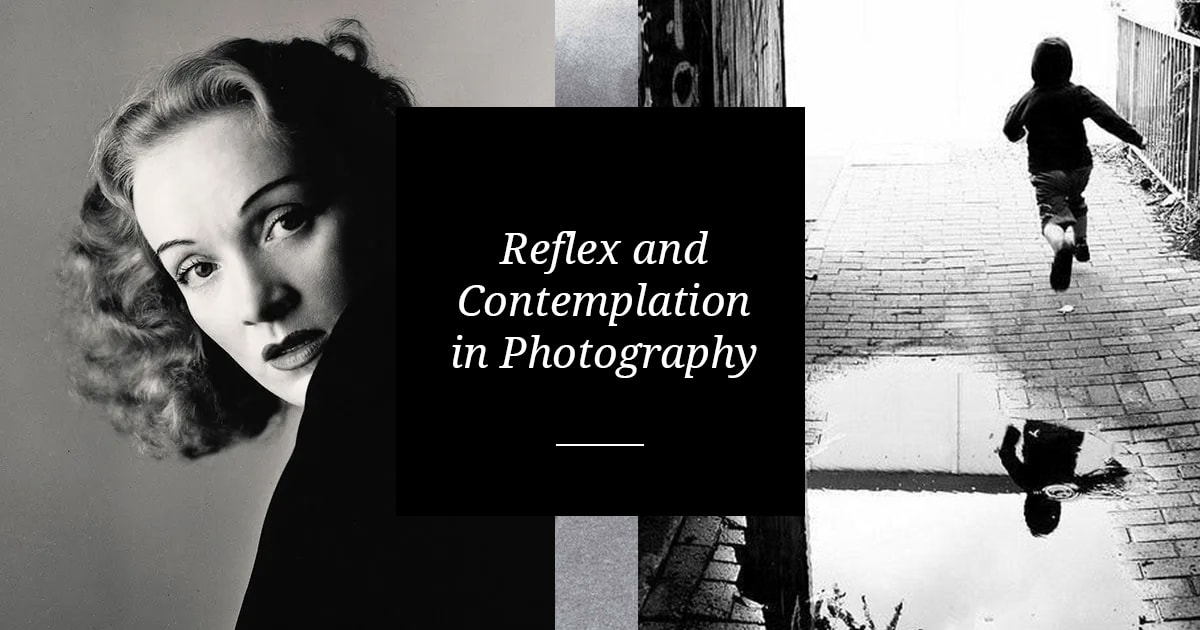

* The cover photo juxtaposes two iconic images: on the left, a contemplative portrait by Irving Penn, and on the right, a dynamic photograph by Cartier-Bresson. Each captures a distinct “speed” in photography: Penn’s work embodies contemplation, while Cartier-Bresson’s exemplifies reflex. Both remain intentional.